If you think the Middle East is complex today, go back a thousand years.

📍 Syria, early 11th century.

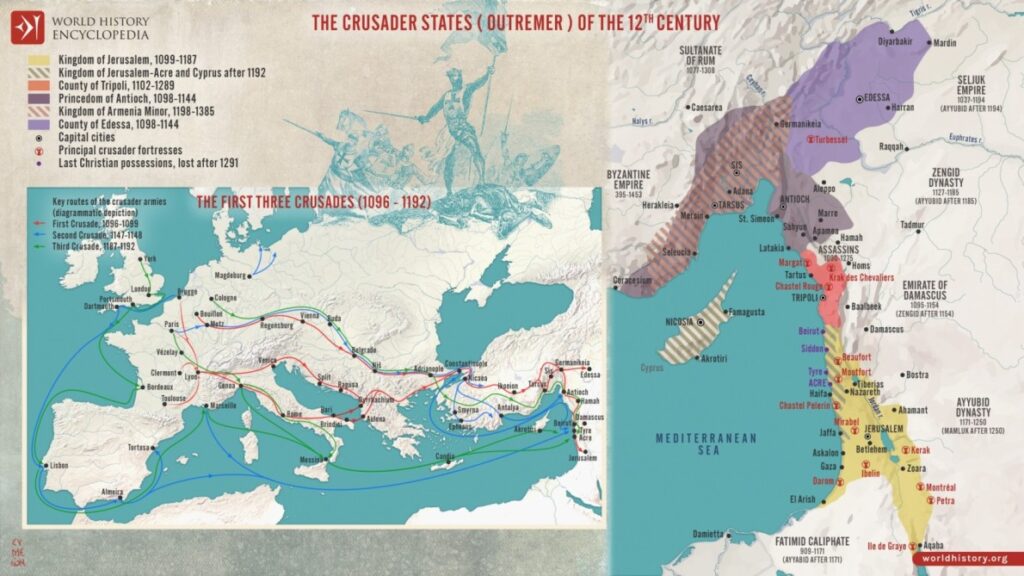

At the time, it was not a single country—it was a patchwork of powers.

Local emirs ruled cities like Homs, Damascus, and Aleppo, each with their own armies, taxes, and ambitions.

Meanwhile, in the north, the Byzantine Empire hovered like a shadow.

To the east, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad was still a symbol of unity, but its control was weakening.

At the same time, along the Mediterranean coast to the west, Fatimid Egypt held sway.

In short, there was no peace. There were no national borders as we know them. And everyone wanted the same thing: control of trade routes, access to water, dominance over religion, and security from the next invasion.

Then, add something new to the mix:

A surge of warriors from Europe—fueled by religion, opportunity, and the promise of land.

These were the Crusaders.

Why the Crusaders Came

At the end of the 11th century, the Pope in Rome called on Christians to reclaim the Holy Land. That call became the First Crusade (1096–1099), and it changed the region forever.

However, their goal wasn’t just Jerusalem. It was about gaining influence in the rich eastern Mediterranean. After all, these knights and nobles weren’t only religious men—they were political thinkers, skilled in war, and deeply aware of power.

Specifically, they wanted:

- Access to the spice and silk trade routes coming from Asia.

- A foothold in the wealthy cities of the East.

- Strategic castles to protect what they had won.

In other words, they didn’t come for a short trip. They came to stay.

And Syria? Syria was right in the middle of everything they wanted.

What Syria Looked Like Then vs. Now

Today, Syria is one nation. But in the 11th and 12th centuries, it was not. It was divided, fiercely independent, and unstable—similar, in some ways, to parts of the world today that are divided by militias, shifting alliances, and competing regional powers.

Geographically, the land was fertile. The coast offered trade. The interior gave access to larger empires. Whoever could hold the middle—the Homs Gap—could control the flow of goods, armies, and influence between the sea and the cities.

That’s precisely why castles mattered so much. And ultimately, that’s why Krak would soon rise.

Think of It Like This:

If you wanted to build a military base today, you wouldn’t put it just anywhere.

To start, you’d find a crossroads. Then, you’d pick high ground. Next, you’d make sure you could see and control everything around you.

First, you’d need to protect your people. You’d need food, water, horses, communication. You’d plan for attack and supply.

That’s exactly what the Crusaders did when they found an old Kurdish fort sitting quietly on a hill in western Syria.

And from that starting point… they built one of the most advanced military fortresses of the medieval world.

Now that you understand the world outside Krak, it’s time to explore what made it nearly untouchable from within.

“A great fortress doesn’t rise from nowhere. It rises from need.”

A Fortress Built from Layers of Power

When the Crusaders reached the Kurdish fort on the hill in 1142, they didn’t tear it down. Instead, they saw what it was—and more importantly, what it could be.

Strategically, the hill overlooked everything: farmland, valleys, and the road between Homs and Tripoli. The Knights Hospitaller, one of the most powerful military orders in the Crusader world, took it over. And rather than simply reinforce it, they turned it into something entirely new.

What followed became known as Krak des Chevaliers, or “Castle of the Knights.” It was no longer just a watchtower. Instead, it became a statement of control, a shield for Crusader territory, and a launchpad for power.

But what made this castle so good?

It wasn’t just the stone. It was how every part of it served a purpose, and how every part of it worked together.

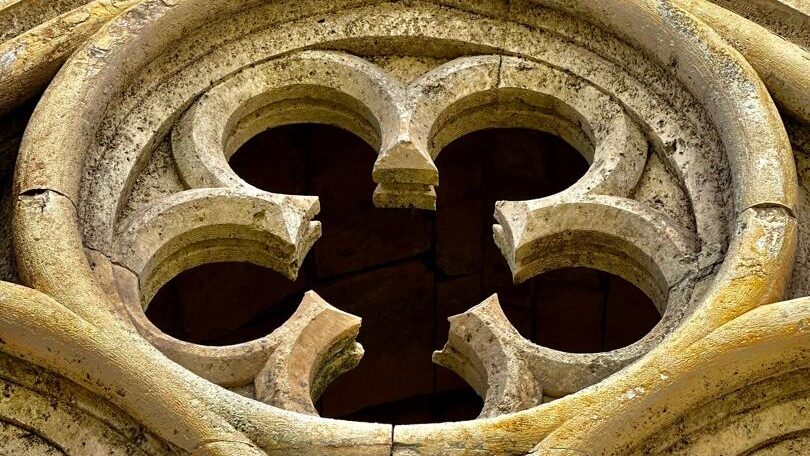

A Wall That Tells Its Own Story

Walk up to the wall and take a good look. Right away, you’ll notice something strange. The lower stones are black and heavy. The ones above are smooth and white. Higher still, the patches are warmer in color—golden, almost sandy.

But these are not signs of damage or repair. Rather, they’re chapters in Krak’s history.

- The black basalt? That’s the original Kurdish foundation—built in 1031.

- The white limestone? That’s Crusader craftsmanship from the 12th and 13th centuries.

- The golden sandstone? That’s from the Mamluks, who took the castle in 1271 and made it their own.

In truth, you don’t need a textbook to understand this. The stones speak for themselves. You are literally seeing the fortress change rulers before your eyes.

“To touch the wall at Krak is to touch three empires in one place.”

Clearly, this castle wasn’t built once. Instead, they built again and again—each time stronger, smarter, and more adapted to the needs of the time.

The Logic Behind the Walls

Most castles have one wall. But Krak has two.

The outer wall is thick, round-towered, and intimidating. However, it’s only the first line. Behind it is a second wall—even taller, even stronger.

This was called concentric defense—a smart system where the inner fortress could keep fighting even if the outer wall was lost.

And what lay in between those walls? A narrow open space. Anyone who made it through the first layer would find themselves trapped in a kill zone, attacked from all angles.

Even the entrance was designed to slow enemies down. There’s no direct path. The main corridor twists and turns. It’s narrow. It’s steep. Meanwhile, defenders stood above it, using holes in the ceiling to drop rocks, arrows, or boiling oil.

In short, this castle doesn’t just stop you. It wears you down, before you even get close to the people inside.

A Ramp Made for War

Most castles rely on stairs. But Krak doesn’t. It has a vaulted stone ramp that winds upward—wide and smooth enough for horses.

As a result, a knight on horseback could go from the outer courtyard to the upper towers without ever dismounting. That’s rare. And it’s brilliant.

This design meant fast response. It meant cavalry could move inside the walls—quickly, safely, and fully armed.

Importantly, this wasn’t for show. This was a functional design for a fortress that expected siege, ambush, or surprise attack at any moment.

It also connected the stables below, where they used to keep up to 300 horses, to the heart of the castle. In short, every detail was connected: movement, shelter, defense.

“Speed in a fortress is not luxury—it’s survival.”

A Castle Built for Living

A lot of people think castles are cold. But Krak is different.

It was more than a fortress. It was a community. Around 2,000 people lived here—knights, blacksmiths, cooks, carpenters, servants. And importantly, the design reflects that.

The castle’s kitchen had a massive oven—its inner walls still blackened from centuries of fire. Additionally, there were latrines with stone chutes leading outside the walls—smart waste management long before plumbing.

There were also cisterns to catch and store rainwater—one open and one covered. In fact, the water system used gutters and channels built into the architecture.

Beyond that, the castle has a bakehouse, a great dining hall, and storage vaults for food and equipment. Everything needed for months of siege was stored in quiet readiness.

The pavement stones beneath your feet are still worn from generations of boots, hooves, and wheels. They serve as a reminder of daily life, of routine inside the walls.

Krak wasn’t just a battlefield. It was a city under armor.

A Chapel That Became a Mosque

In the heart of the inner ward, you’ll find a chapel. Crusaders built it after 1170—a narrow building with barrel-vaulted ceilings and carved stone benches.

At the time, it once held frescoes, colorful paintings of saints and scripture. More recently, a Hungarian archaeological mission removed the frescoes. What remains today is empty stone—but not silence.

Because after the Mamluks took Krak in 1271, they didn’t destroy the chapel. Instead, they added to it.

Two mihrabs—small wall niches facing Mecca—were carved alongside the original Christian altar.

Ultimately, this room tells a quiet truth: religions passed through this space like rulers did. It didn’t become less sacred. Rather, It became layered.

The Siege That Changed Everything

In 1271, Sultan Baibars led a Mamluk army to Krak. He brought engineers, trebuchets, and time.

After weeks of bombardment, the outer wall got sever damage. However, the inner fortress stood firm. The knights held their ground.

So, Baibars tried something else.

He sent a letter, not with threats, but with authority.

The letter claimed to be from the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, based in Tripoli. Ordering the garrison to surrender, it brooked no resistance. It also promised safe conduct. Furthurmore, it bore a seal that looked official. The language was familiar. The soldiers believed it.

In the end, they opened the gates—but it was fake.

Historians believe that one of Baibars’s scribes wrote the letter—or possibly even his cook, who knew Latin. Either way, the trick worked.

“A castle can withstand stone, but not a lie that looks like truth.”

Krak fell not in blood, but in belief.

Why Saladin Failed

Back in 1188, Saladin himself tried to take Krak. He couldn’t.

His men felt desperate. The castle was too strong. The hill too steep. The defenders too ready. He camped, scouted, and left.

Crucially, that failure matters. Indeed, it tells us that Krak was so well designed, so well placed, so well supplied, that even one of the greatest commanders of the age turned back.

In contrast, Baibars didn’t outfight Krak. He out-thought it. And that’s the only way in.

From Fortress to Heritage

Over the centuries, Krak changed hands until, by the early 1900s, villagers had moved in—raising animals and tending gardens in its old courtyard.

Then, in 1933, the Syrian government—with help from the French—moved those families out and began preservation.

Eventually, in 2006, Krak des Chevaliers became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

But then war returned. In 2013, during the Syrian civil war, shells hit the castle and damaged the chapel. Some walls fell.

Still the heart of Krak held. And Today restoration continues—stone by stone.

Why Krak Still Matters

Krak des Chevaliers isn’t just an old stone fortress. Rather, it’s a blueprint—for how people protect, adapt, and survive.

So, it shows how the land decides history.

It proves that design can be defense.

It reminds us that it is easier to break trust than to break walls.

And it teaches that even after war and ruin, something strong can still be rebuilt.

You walk through Krak and you see strength. But more importantly, you see intelligence. Not just in architecture—but in the way people lived, planned, fought, and remembered.

“Krak wasn’t built just to stand but to understand.”

And once you’ve seen it, you’ll never look at a wall, a door, or a ramp the same way again.