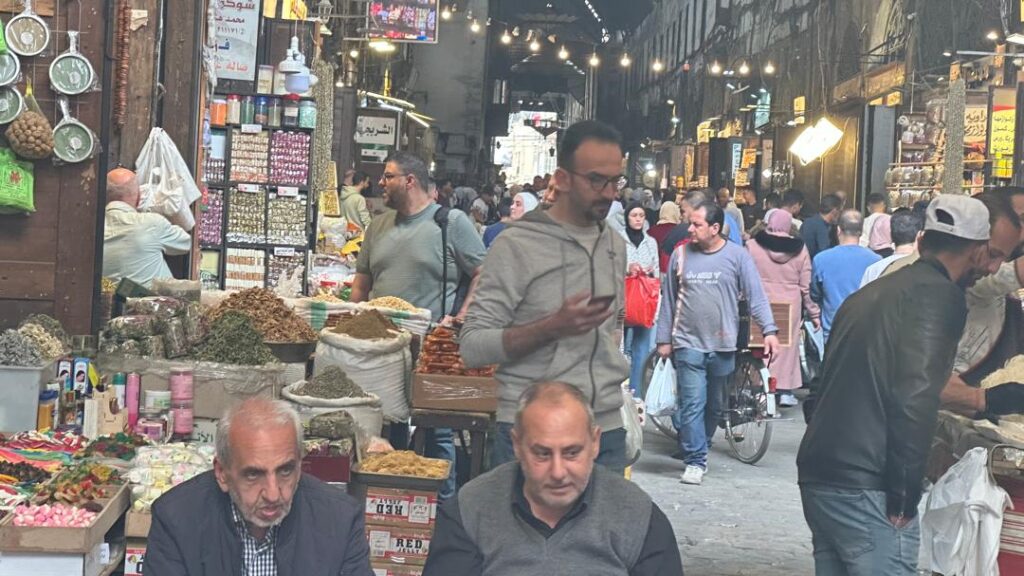

Al-Buzuriyyeh is the Old City’s spice-and-sweets street. It sits just south of the Umayyad Mosque, on the line of the old Roman east–west road that locals today call “Straight Street”. The lane is short—about 150 meters—straight, covered, and busy. Most shops sell what Damascenes use every day: spices, herbs, seeds, nuts, dried fruit, coffee, rose and orange-blossom waters, tahini, halva, and laurel/olive-oil soap. You are not walking a souvenir alley; you are walking the city’s pantry.

A simple history you can carry with you

The name comes from buzur or “seeds” in Arabic, because this was once the place for grains and seeds. Over time it added herbs, perfumery items, and foods you can store and carry. The lane grew strong in the Ottoman period when the city’s governor Asʿad Pasha al-Azm built a huge caravanserai right on it in the 1750s. Goods arrived with caravans, slept under the domes of the khan, and moved a few steps to the shopfronts the next morning. That is still the logic of the street today.

A few meters from the lane stands Azm Palace, the best example of a grand Damascene house. It became a museum in 1954 and later won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1983) for its careful restoration after heavy damage in the 1920s. Next to it, Khan Asʿad Pasha—the largest caravanserai in the Old City—was restored in the 1990s and was formally reviewed on site by the same award program in the 1980s. In one short walk you can see how people lived (the palace), how goods moved (the khan), and how they are sold (the lane).

How to picture the lane before you go

Stand at the mosque’s south side and look down: one straight corridor of shops. Halfway along is a tall stone gate to Khan Asʿad Pasha. A little further, almost hiding between shops, is the door to Hammam Nur al-Din, a working 12th-century bathhouse built in the time of the ruler Nur al-Din. Inside are a changing hall and a sequence of warm and hot rooms under domes pierced with small round openings for light and steam. It is still in use, with men’s and women’s hours. Bring small cash, ask the hours at the door, and expect a simple routine: change → warm room → hot room → wash → tea.

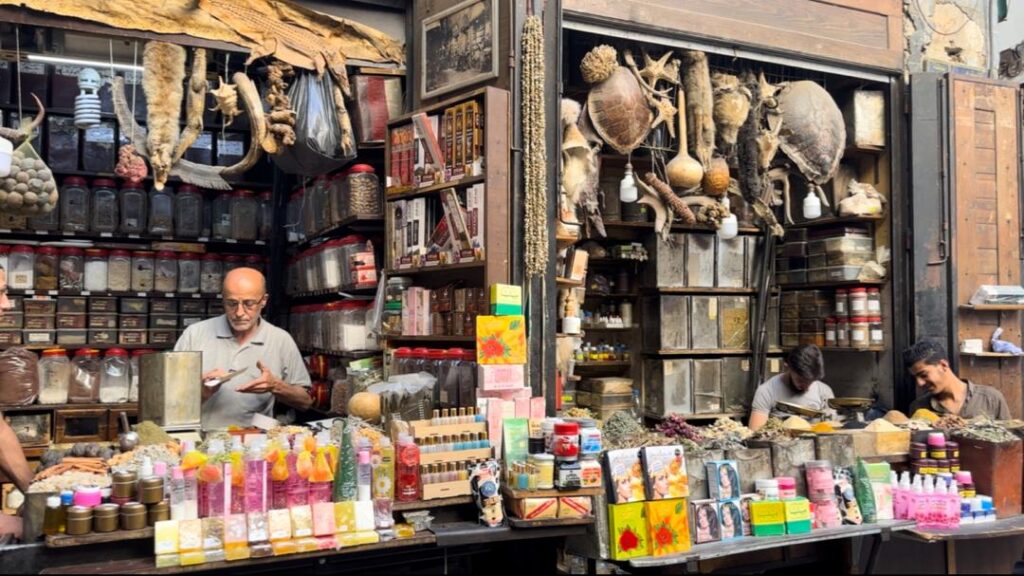

What to look for

Spices and seeds.

You will see open sacks and glass jars: cumin, coriander, nigella, sesame, anise, fenugreek, black pepper, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, nutmeg, turmeric, and the red staples—Aleppo pepper (mild, fruity heat) and sumac (lemony). Smell before you buy. Fresh spice smells clear and bright, not dusty. Ask for blends people actually cook with: za’atar (thyme-sesame-sumac) for bread and tomatoes; seven-spice for rice and meat; and shawarma mixes tuned for chicken or beef. Most merchants will measure in 100-gram units. Buy small amounts (100–200 g) so flavors stay fresh at home.

Herbs and everyday mixes.

This is the home of zhourat shamiyeh—Damascus herbal tea. Shops make it in many ratios, often with chamomile, rose, thyme, sage, anise, fennel, and other simple ingredients. Locals use these blends first for light issues—calming, a sore throat, a winter cold—before they think of a pharmacy, and many visitors pick up a labeled mix for home. Ask the seller to write brewing notes on the bag (e.g., one teaspoon per cup, steep five to seven minutes). This habit of buying herbs for everyday health is well documented in local reporting and culture pieces about the market.

Sweets that define the lane.

Two products carry Damascus with them:

- Qamar al-Din — flexible sheets of apricot leather made in the orchards around Damascus (Ghouta). People dissolve it into a drink, especially in Ramadan, or cut it into strips for dessert. Choose sheets that are supple and glossy, not brittle.

- Malban — a chewy sweet made from grape juice or grape molasses thickened with starch (sometimes a little semolina), often stuffed with walnuts, then dusted so it does not stick. Ask for a small taste and choose your preferred firmness and nut level.

Waters, soaps, and pantry gifts.

Bottles of rose water and orange-blossom water for desserts and tea; stacks of Aleppo laurel soap and olive-oil soap; jars of sesame paste (tahini) and blocks of halva. These pack flat, travel well, and you will use them at home.

How to shop without stress

Walk the lane once to learn, then walk back to buy. Choose one or two shops you liked rather than sampling everywhere. Ask prices per 100 grams. Watch the scale. Ask for sealed bags and labels in English and Arabic. For rose or orange-blossom water, choose sealed bottles and ask them to tape the cap. For malban and qamar al-din, ask for extra wrapping so they do not stick to other things in your bag. Mid-morning or late afternoon is usually easiest; Fridays often start slower after midday prayers. Wear closed shoes—the stone is smooth and can be slick after a rain.

If you cook, bring a small list of dishes you like; merchants will tailor a spice mix for it. If you do not cook much, ask for three things you will use without effort: 1) a za’atar blend, 2) Aleppo pepper, 3) sumac. With these three jars you can change how bread, eggs, salad, and grilled meat taste at home in seconds.

Two doors you should step through

Khan Asʿad Pasha.

Go through the tall gate in the middle of the souq. Stand at the fountain and look up. Nine drum-lit domes bring a soft light into the courtyard; black-and-white ablaq arches ring two levels of bays; a grid of piers shows how goods and people were organized. The khan covers about 2,500 m² and was built in 1751–1752 (some official sources say completion in 1753). It was restored in the 1990s and is regularly cited as the largest khan in Damascus. Even a two-minute visit helps you “read” the market outside: goods came in, rested here, and then moved out to the lane.

Hammam Nur al-Din.

Between spice shops sits a bathhouse from the 12th century. The plan is classic: a large changing hall, then warm and hot rooms under domes with small circular openings. It is often described as the oldest functioning hammam in Damascus, and it sits exactly where a bathhouse adds value—in the market, next to work and trade. If you go, ask at the door about men’s and women’s hours, bring small cash, and keep the routine simple: change, warm up, heat, wash, tea.

Why this lane still matters

The souq’s life is not only the goods; it is also the people who keep it steady. Many shops are family-run and have been here for generations. Local heritage writing notes that you still meet the same families on the same stretch, passing down how to select, dry, store, and mix herbs and spices. One name you may hear is the Darkal family, known for herb work and traditional blends—an example of how university-educated sons and daughters often return to the counter because that is where the real knowledge sits.

This resilience is part of the market’s identity. Even after hard years, reporters visiting the Old City describe Al-Buzuriyyeh returning to its core trade: herbs, spices, scented waters, soaps, and house sweets. That is why the lane feels practical, not staged—it sells the same useful things to residents and visitors.

Short, clear tips that make your visit easier

- Etiquette. Most sellers are fine with photos of goods; ask before photographing people. Greet the shopkeeper. A smile and a short chat go a long way.

- Tasting. It is normal to taste a nut or a small piece of malban or a pinch of spices before buying.

- Allergies. Many mixes contain sesame or nuts. If you have allergies, say so clearly.

- Bargaining. Prices are usually posted. If not, ask gently, and if you are buying several items, ask, “Any better price if I take two?”

- Packing. Vacuum-seal if you can. Ask for double bags for powders and for tape on bottle caps.

- Timing. Mid-morning or late afternoon. Fridays can be slower around prayer time and few shops open later.

- Health note. Herb uses above reflect local custom and are not medical advice. If you have a condition or take medication, consult a doctor.

A simple loop so you don’t get lost

Start just south of the Umayyad Mosque and enter Al-Buzuriyyeh. Walk slowly to the khan and step inside. Come back out and continue to the bathhouse door. Finish at Straight Street (the old Roman road). Then turn around and make your buying pass back toward the mosque. In 40–60 minutes you will have seen everything without rushing.

What to bring home (that you will actually use)

- Za’atar for bread and tomatoes.

- Aleppo pepper for eggs, pizza, grilled meat, and soups.

- Sumac for salads and roasted chicken.

- Qamar al-Din sheets for drinks and desserts.

- Malban with walnuts for tea time.

- Rose or orange-blossom water for tea and simple sweets.

- Aleppo laurel soap for a small, easy gift.

Nearby places that complete the picture

Umayyad Mosque.

The reason this area feels like the city’s heart is simple: for centuries, daily life in Damascus has flowed between prayer and market. Ibn Battuta wrote about the mosque and the bazaars by its walls when he visited in 1326, linking the two as one experience. When you step from the mosque into the lane, you are repeating an old habit.

Azm Palace (house-museum).

Go for the courtyard plan: a central fountain that cools the air, orange and bitter-orange trees, painted ʿajami rooms, and a winter wing/summer wing that shows how houses were designed to breathe. The palace’s restoration won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1983) and is a model for how to conserve a lived-in historic building.

Khan Asʿad Pasha (caravanserai).

Look for the domes with circular openings, the black-and-white arches, and the two-level ring of bays. This is the Old City’s largest khan, started in 1751 and completed a couple of years later; restoration in the 1990s made it visitable again and preserved the sense of a working logistics hub in the middle of a market street.

Hammam Nur al-Din (working bathhouse).

A good reminder that a city’s comfort matters as much as its trade. It is still used; it still sits in the right place—inside the market—because workers and shoppers once went straight from the lane to the steam.

Voices that noticed this place

Writers have walked into Damascus through its markets for centuries. Mark Twain looked down on Damascus and wrote: “Go back as far as you will into the vague past, there was always a Damascus,” a line he used to explain why the city feels older than the empires around it. Gertrude Bell wrote about Damascus with its gardens, domes, minarets, and bazaars as the living fabric of the city. Ibn Battuta linked the great mosque and the surrounding markets as a single experience for a traveler. If you stand in Al-Buzuriyyeh and turn north toward the mosque, you are standing in the scene they described.

Clear answers to common questions

How old is the market I am walking through?

As a named lane, Al-Buzuriyyeh took shape over the last few centuries, gaining strength in the Ottoman period when Khan Asʿad Pasha was built right on it. Its line, however, follows the older street plan of the Roman city, which is why it connects so neatly to Straight Street.

Why is this lane so close to the mosque?

In many Islamic cities, the great congregational mosque and the markets around it grew together. Damascus is a classic case: prayer space, learning, and trade within a few steps. Ibn Battuta’s account shows this was already normal in the 1300s.

Is the bathhouse really inside the market?

Yes. Hammam Nur al-Din is a working bath built in the 12th century and set among the shops. That placement—right where people work and buy—explains why hammams lasted: they served daily life.

What should I buy if I only have ten minutes?

One small za’atar, one Aleppo pepper, a packet of sumac, a sheet of qamar al-din, and a piece of malban with walnuts. You will use all of them at home.

What should I look at even if I am not buying anything?

The domes and arches of Khan Asʿad Pasha and the courtyard plan of Azm Palace. Ten minutes in each will change how you read every street around you.

A few product notes so labels make sense later

- Za’atar = a thyme-sesame-sumac blend used on bread and salads.

- Aleppo pepper = mild, fruity red chili flakes used like paprika with a touch of heat.

- Sumac = sour red powder that gives a lemon kick to salads and chicken.

- Zhourat = a Damascus herbal tea mix; ask for brewing notes.

- Qamar al-Din = apricot leather sheets from the orchards around Damascus.

- Malban = grape-based chewy sweet, often walnut-filled.

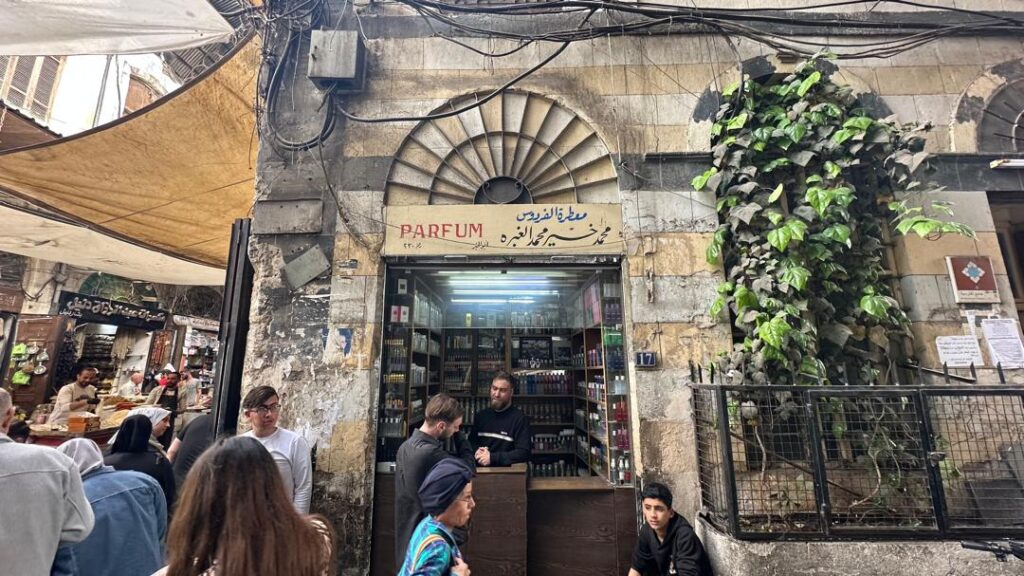

- Attār = a shop selling herbs, scented waters, simple oils, and related goods.

What makes this street special

It is compact, useful, and layered. You can stand at one point and see a market, a bath, a grand house, and a caravanserai—each one still readable in its original role. The goods are not props; they are what kitchens and homes use. The families you meet are not actors; they are merchants and blenders whose names appear in local histories of the market. Visitors write about Damascus as a city that feels older than empires; Al-Buzuriyyeh is the small, everyday proof of that idea.

Plan in one glance

- Where: south of the Umayyad Mosque, on the line of the old Roman east–west road (“Straight Street”).

- Length: about 150 meters, covered and straight.

- Anchors: Khan Asʿad Pasha (mid-18th century; biggest khan), Azm Palace (house-museum; Aga Khan Award 1983), Hammam Nur al-Din (12th century; still functioning).

- What to buy: za’atar, Aleppo pepper, sumac, zhourat, qamar al-din, malban with walnuts, rose/orange-blossom water, laurel soap.

- How to shop: learn on the first pass, buy on the second; ask prices per 100 g; seal and label; pack liquids tight.

- When: mid-morning or late afternoon; Fridays often slower after prayer.

If you want a last word from a traveler

Mark Twain, after months of dust and heat, looked down over Damascus and wrote: “Go back as far as you will into the vague past, there was always a Damascus.” Walk Al-Buzuriyyeh with that line in mind. You will see why a straight market street, 150 meters long, can carry so much of a city’s memory.

Sources you can check quickly

- Market location, length, and goods; alignment with Straight Street. (Wikipedia)

- Khan Asʿad Pasha: area, dates, restoration, “largest khan” notes. (Wikipedia)

- Azm Palace: museum history and Aga Khan Award (1983). (archnet.org)

- Hammam Nur al-Din: 12th-century origin and setting inside the market. (Islamic Art Museum)

- Family continuity and market culture (including names you hear on the lane). (Syrian Heritage Archive)

- Traveler voices: Ibn Battuta on mosque + markets; Mark Twain’s Damascus line; Gertrude Bell on Damascus bazaars. (Dickinson Blogs)