Long before great cathedrals rose over Europe, before domes glittered under Byzantine mosaics, and before church bells marked the hours of faith, there was a quiet house standing on the edge of the Syrian desert. It was not built to impress or to rule; it was a home. Yet in the early third century, this modest dwelling became something extraordinary. It was transformed by faith into the world’s first known Christian church — a place where some of the earliest followers of Christ gathered in secret to pray, to sing, and to baptize. That house, buried for centuries beneath the sands of eastern Syria, is now known to history as the Dura-Europos Church, the oldest surviving church building ever discovered.

When archaeologists uncovered it in the 1930s, the world of early Christianity suddenly became tangible. For the first time, scholars could see not only how the earliest Christians lived, but how they worshipped — in small, intimate gatherings where the walls themselves bore witness to their beliefs. The church lies in what was once the Roman frontier city of Dura-Europos, perched above the Euphrates River. Founded by the Seleucids and later ruled by the Parthians and Romans, it was a city of mixed peoples and religions — Greek, Aramaean, Jewish, and Persian — where temples to many gods stood side by side. Amid this diversity, a small community of Christians quietly adapted one of their homes into a sacred space between 233 and 256 AD, long before the faith was legalized by Constantine.

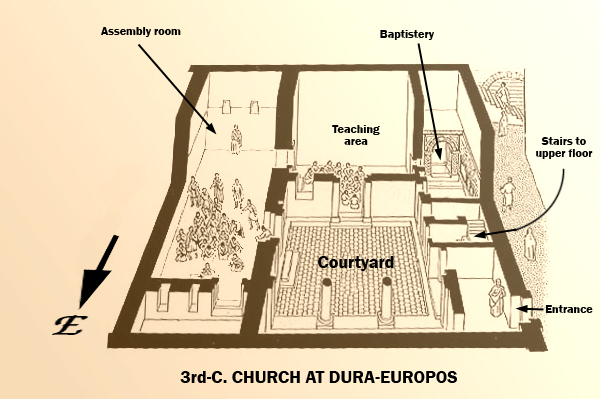

Inside, the transformation was simple but deliberate. Two small rooms were joined to form a single large hall where believers could gather for communal worship, listen to scripture, and share meals of fellowship. Another room became a baptistry, the spiritual heart of the house. There, a basin was built for the ritual of baptism — the moment when new converts entered into the Christian faith. The rest of the house likely served as living space, meeting area, and perhaps even shelter for travelers or members of the community.

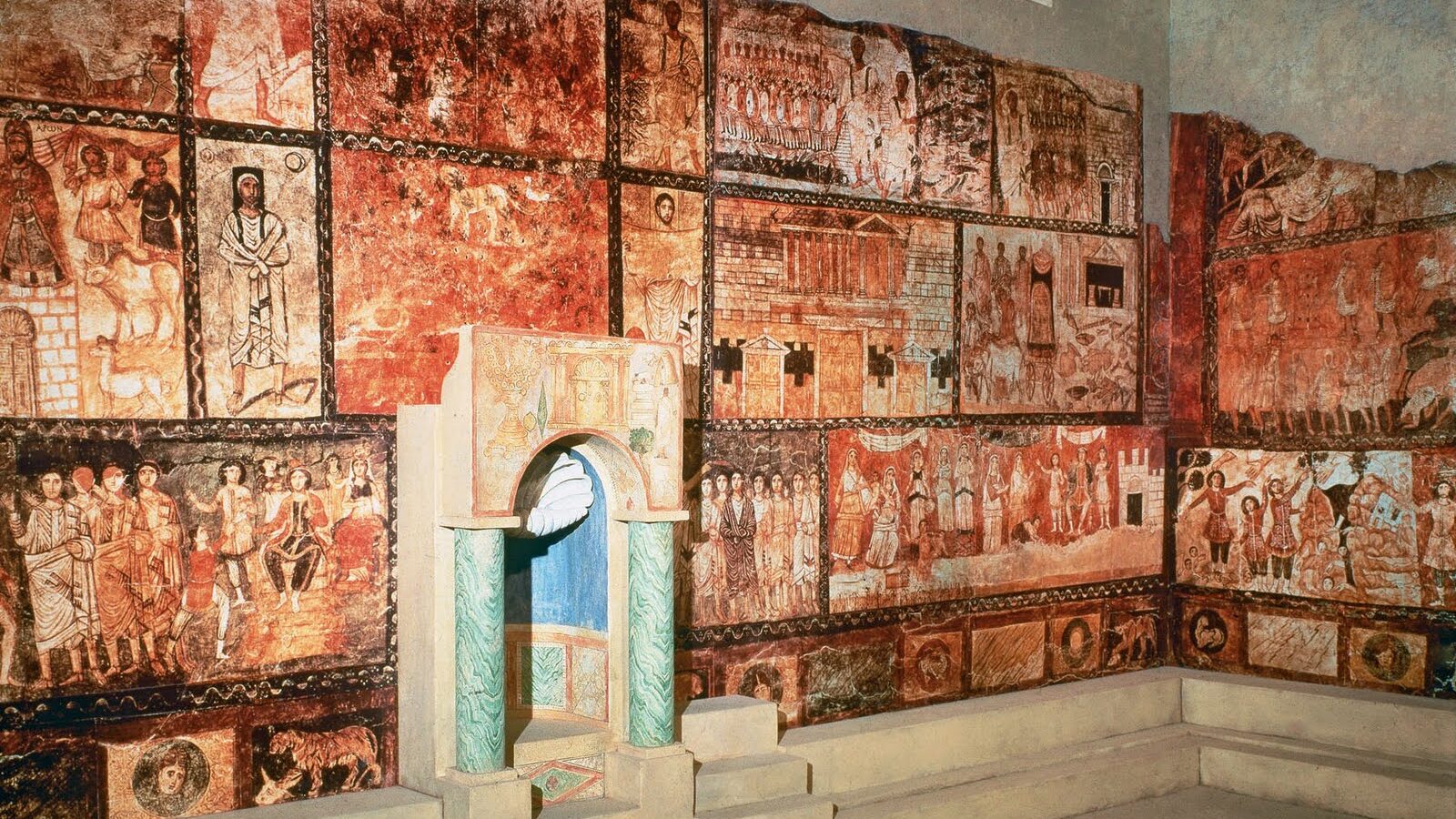

The Dura-Europos Church was not meant to impress the eye; it was meant to protect the spirit. Christianity in the third century was still a persecuted religion. Believers gathered quietly, away from public temples and civic spaces. Yet, in that modest house, something remarkable happened — art was born. On the plastered walls of the baptistry, archaeologists found the oldest surviving Christian paintings in the world. These frescoes, still visible after nearly 1,800 years, depicted the faith’s most central stories: the Good Shepherd carrying a lost sheep; Christ and Peter walking together on water; the healing of a paralytic man; and three women approaching a tomb at dawn — perhaps the earliest artistic portrayal of the Resurrection.

One of the most intriguing images shows a woman beside a fountain, her gesture calm, her face serene. For decades, scholars debated who she might be. Some believed she represented the Samaritan woman at the well. Others, looking closer at her posture and context, proposed that she could be the Virgin Mary, making this the oldest known image of her in existence. The style of the paintings is simple, almost childlike, yet filled with quiet power. They were not created for beauty, but for meaning — visual symbols that would have spoken deeply to those who entered the baptistry, ready to begin a new life through faith.

The church’s story, however, might have ended there if not for an accident of war. In 256 AD, the city of Dura-Europos came under siege by the Sassanian Persians, the powerful empire to the east. As Roman soldiers prepared their defenses, they built an enormous earthen ramp up against the city’s western wall — directly over the small Christian house. The ramp, intended for battle, became the church’s salvation. It buried the building completely, sealing it in layers of packed soil. When the city eventually fell and was abandoned, the church remained hidden, untouched and forgotten, for nearly seventeen centuries.

When French and American archaeologists began excavations at the site in the 1930s, they uncovered a time capsule of ancient faith. Beneath the dust, they found walls still bearing the color of the frescoes, inscriptions in Greek and Latin, and faint traces of the lives that once animated the space. Names like Proclus and Paulus were scratched into the plaster, perhaps belonging to Roman soldiers or local converts. One inscription even provided a date in the old Seleucid calendar, corresponding to 232–233 AD — an almost miraculous clue that allowed scholars to date the building precisely.

What makes the discovery even more fascinating is its setting. Just a few meters away stood one of the most beautifully preserved ancient synagogues ever found, adorned with vibrant murals depicting scenes from the Hebrew Bible. The juxtaposition is astonishing — two places of worship, one Jewish and one Christian, standing side by side in a city that thrived on cultural and religious diversity. Together, they tell a story of coexistence in a world often imagined as divided.

The Christian house, modest as it was, would go on to reshape the study of early Christianity. Before its discovery, historians had little physical evidence of how Christians worshipped before the great basilicas of Rome or Constantinople. The Dura-Europos Church showed that worship was domestic, intimate, and profoundly communal — that the roots of Christianity grew not in marble halls, but in living rooms, courtyards, and whispered hymns shared among friends.

Today, the frescoes that once adorned the baptistry walls are preserved at Yale University’s Art Gallery, where they remain a centerpiece of early Christian archaeology. Sadly, the original site has suffered from looting and damage during recent conflicts in Syria, and its current condition is uncertain. Yet even if the structure itself has been lost, the story it tells continues to resonate. It is a story of faith surviving through fragility, of beauty hidden in simplicity, and of a small community whose courage helped lay the foundation of a global religion.

Fun Facts about the World’s Oldest Church

- The Dura-Europos Church was discovered in 1931 by a joint French–American archaeological team.

- It is the oldest surviving Christian church building in the world, dating from between 233 and 256 AD.

- The building was originally a private home converted into a place of worship — what historians call a domus ecclesiae, or “house church.”

- Its preservation is due to an accidental burial under a Persian siege ramp in 256 AD.

- The church’s baptistry paintings are the earliest known examples of Christian art, centuries older than those in Rome or Ravenna.

- One fresco possibly depicts the Virgin Mary, making it the oldest image of her ever found.

- Nearby, the Dura-Europos Synagogue also preserves ancient murals, making the city one of the richest archaeological sites for early Abrahamic worship.

- The site lies near the modern Syrian village of Salhiyé, overlooking the Euphrates River.